Native Willows, Red-osier dogwood and Black Cottonwood (or Balsam poplar) are very common in western Canada. The collection of cuttings is described here.

Note that although this information is most relevant to the Kootenay region of B.C., as this is where the example harvest areas shown are located, it is generally applicable to other parts of western Canada as well.

When to Harvest Live Cuttings

Live cuttings should be collected while the trees or shrubs are in a dormant state (late fall to early spring). This is when the energy and nutrient stores within the woody stems are highest, and therefore the greatest chance of successful establishment after planting is obtained.

It will be noted that some willow species produce catkins very early in the spring, before the appearance of leaves (e.g., Scouler’s willow). It is ok to collect cuttings of these species after some catkins have appeared. However, if flowering is well advanced and leaf buds are opening the ideal period for harvesting is over.

Harvesting Locations

When collecting live cuttings of willow, Red-osier dogwood and Cottonwood it is important to consider the location of the harvest site with respect to the area in which the cuttings will be planted. This means that material should not be transferred up or down in elevation, or east/west or north/south to an excessive degree. As to what constitutes an acceptable degree of stock transfer, there are no recognized standards or guidelines. In general the live cuttings should be from a similar elevation (e.g., ± 100-200 m) and from the same geographical area and ecoregion (e.g., biogeoclimatic zone). Also see Movement of Plant Material.

Willow

Willows grow in a variety of habitats ranging from very wet to considerably dry. In the southern interior of B.C. there are over 20 native willow species. These can be difficult to identify as there is high intra-species variability and also a high propensity to form hybrids (see ref. 1 below). In addition, during the winter months when live cuttings are collected, there are no leaves or catkins to aid in identification. With experience, however, the twigs and buds can be fairly distinctive. The type of site on which the willow is growing is also an important indicator of the potential species present.

When using willows in ecosystem restoration it’s more important to know the site from which the cuttings are harvested is ecologically similar to that on which they will be planted – than to know the actual species being collected (see ref. 2 below). This is providing collection is from native species and not something exotic or introduced.

One way to help identify dormant willow is to bring branch ends indoors and place them in a vase of water, or alternatively just place them in a bucket of water outdoors. Catkins (and possibly also leaves) will eventually appear. Remember that male and female catkins appear on separate plants.

Red-Osier Dogwood

Red-osier dogwood is a riparian species that is often seen in dense thickets along streambanks, and in other moist or wet areas. It is also found in upland locations, generally in drainage and seepage areas.

Unlike the more light-demanding Willows and Cottonwood, Red-osier dogwood is moderately shade tolerant. This species can therefore be planted on sites where there is partial shade due to an overstory of larger plants. It is also ok to collect dogwood cuttings from partially shaded areas, however areas with deep shade should be avoided. This is because plants growing in fuller sunlight will have higher energy reserves.

As a moisture-loving species dogwood should not be planted on dryer sites.

Black Cottonwood

Black Cottonwood, and the closely related species Balsam Poplar (Populus balsamifera) that has a more eastern/northern distribution (the two species also form hybrids), has a very wide ecological amplitude. This means it does well on a wide range of sites, ranging from very wet to considerably dry (it is recommended that in the interior of B.C. soil bioengineering projects on dryer sites should a have a substantial or even majority component of cottonwood).

Disturbed areas such as along roadsides or around old gravel pits are some of the best locations to collect cuttings of this species. Here dense stands of evenly aged and similarly sized material may form, making collection fast and efficient.

Size of Material to Collect

When collecting live cuttings for use in soil bioengineering treatments, no material less than about 2 cm diameter at the tip should be used. There is no maximum diameter as long as the material is vigorous and disease-free. Very old, decadent material should not be used (this often has split or deeply furrowed bark). Live cuttings larger than about 6 to 7 cm at the base do become very cumbersome to handle and transport, and most willows and dogwood don’t get bigger than this anyways.

When using Cottonwood in soil bioengineering projects on drier sites, some larger size cuttings — up to about 10 cm or more in diameter — can be included. After saturation during the soaking treatment these hold a large volume of water. This may improve their survival on such sites.

In terms of the length of material to harvest, generally nothing shorter than about 60 cm should be collected. I usually collect lengths of 2.5 m. This is a reasonable size to transport and handle and can be used where longer live cuttings are required, or they can be cut into two or three live stakes.

For producing TRS Cuttings, stems between about 2.5 and 5 cm in diameter at the base are generally used, providing these have the required length (usually 2.5 m). Stems larger than this produce stock that is too heavy, and as TRS Cuttings are grown in a moist nursery environment, smaller diameter material is appropriate. I recommend no minimum diameter at the tip, although I always cut the very apex off.

Harvesting Etiquette and Where Not to Harvest

When harvesting on public land (e.g., roadsides) in rural areas it is important to be respectful of the local residents who may be obtaining some screening or aesthetic benefits from the trees and shrubs growing near to their property. If there is any chance of this, either leave the material alone or talk to the adjacent landowner(s).

It is also important that pruned branches be removed from roadsides or trails where they may be an obstruction, and not left in ditches where they might impede water flow.

As a general rule live cuttings should not be collected within about 10 m or so of streams or other potential fish-bearing waters. For the riparian willows and dogwood, there is usually an abundance of appropriate material well away from such areas. Selective harvesting of stems from clumps should also be done in some areas (see below).

Stock Handling

Live cuttings should be regarded as living plant material. This means the cuttings should be handled gently, and be kept cool, moist, and shaded.

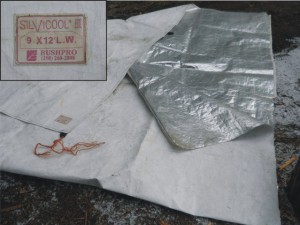

Covering the material with Silvacool tarps starting immediately after harvest is a standard practice – and preferably also in a shady location.

White lumber-wrap material (sometimes free at lumber yards) is a low-cost alternative to Silva-cool tarps, although Silvacool’s are far superior.

Especially if warmer temperatures are transpiring, it is important to thoroughly moisten the material on a daily basis. If snow is available, throwing some over top every day or so is a good idea.

If the material is not soaked and then planted within a week or two after harvest (and depending on temperatures), some form of cold storage is required (see Live Cutting Storage).

Tools and Equipment

When harvesting cuttings to produce TRS Cuttings I collect all my Willow and Red-osier dogwood cuttings, and most of my Cottonwood, manually using a Fiskars 2” PowerGear bypass lopper (to cut the stems and larger branches).

Fiskars Platinum Series PowerGear bypass lopper. The gear-action on this lopper makes cutting stems up to 6 cm in diameter easy. This tool is highly recommended.

This is a very effective tool as stems up to about 6 cm in diameter can easily be cut.

Manual cutting with a Fiskars lopper is fast – and for material ≤6 cm in diameter – easily comparable to harvesting with a chain-saw (especially when the saw maintenance time is factored in). A bypass lopper is also safer to use, more environmentally friendly, and totally silent. This later point is important as often lower elevation live material is collected along roadsides near to rural residences – I have never had any complaints. It is also far more pleasant to harvest manually with loppers than with a chainsaw.

It is also easy to selectively harvest stems from willow or dogwood clumps using a manual lopper, as compared to a chainsaw where this can be tricky (especially if the stems not cut are to remain undamaged). This is especially important when harvesting in sensitive riparian areas. When selectively harvesting live cuttings, only the larger usable stems are taken – meaning the integrity of the clump is maintained.

There are situations where the use of chainsaws is appropriate and more efficient. One example is, as noted above, when larger Cottonwood is wanted for standard soil bioengineering treatments. Also, sometimes larger Cottonwood trees is the only material available. If located in an appropriate area, such as under power lines, these larger trees can be cut down with a chainsaw and only the top portion used. Another situation is along forestry roads where the complete cutting of material may even be desired.

After cutting the material down with loppers or a chainsaw (or even a bow-saw), branches are removed using a hand-pruner. Learning to use both your right and left hand here can greatly reduce the risk of a repetitive strain injury on longer projects.

To facilitate handling of live cuttings the material should be tied into bundles. This is much easier to do if a bundling bench is used. These can be constructed inexpensively out of wood, although benches fabricated from aluminum are superior.

Saftey glasses are an essential piece of equipment when harvesting live cuttings. A good pair of gloves is also required.

Depending on other equipment being used (e.g., chainsaws) and the size of material being cut, there could be other important safety equipment requirements (e.g., hard hat, chainsaw chaps).

Scratch Test

One way to be sure live material collected is vigorous and healthy is to scratch the bark off a small area. A bright green cambium layer should be visible.

References cited:

(1) Parish, Coupé and Lloyd (1996). Plants of Southern Interior B.C. and the Inland Northwest. Lone Pine Publishing. (A highly recommended plant ID book.)

(2) Polster, D. (2002). Soil Bioengineering Techniques for Riparian Restoration.